The Sacred Liturgy

The word “Liturgy” means “the work of God.” It is Christ Himself that works through the Sacred Liturgy. We share in his work by praying, singing and listening. Our active participation at Mass expresses what we believe and helps to deepen our relationship with God. The Holy Sacrifice of the Mass is a singular moment of grace, in fact, it is the greatest prayer we can offer. As St. John Vianney said, “When we go before the Blessed Sacrament, let us open our heart; our good God will open His. We shall go to Him; He will come to us; the one to ask, the other to receive. It will be like a breath from one to the other.” We gather together every Sunday as a faith-filled community, to praise God, to ask God to forgive our sins, to thank God, and to petition God for all we need.

Liturgical Vestments

The clothing the priest wears for mass is called a chasuble. A deacon wears a similar vestment called a dalmatic. Chasubles and dalmatics come in different colors to represent each season and special feasts of the Church year. Green is worn during ordinary time and represents new life. During Advent and Lent, the priest wears a violet chasuble to signify penance and reminding us to turn away from sin. White is worn during the Easter and Christmas seasons, for special feast days and represents joy. Red is worn when celebrating feasts of the Holy Spirit, apostles, and martyrs.

The Entrance

The Mass begins with everyone singing a song of praise to God. During this hymn, the clergy, and the altar servers process to the altar. The deacon (or in his absence a lector) carries the Book of the Gospels in procession symbolizing that it is Jesus Christ who comes into our midst to lead us to the heavenly banquet.

Reverence of the Altar

As the procession approaches the altar, the celebrant and assisting ministers pause to acknowledge the presence of God. They genuflect to the real presence of Christ in the Tabernacle and then the priest and deacon kiss the altar which is a symbol of Christ for He sacrificed Himself for each and every one of us. On special occasions the altar may be incensed. The sweet aroma of incense symbolizes something pleasing and acceptable being offered to God and its smoke symbolizes the prayers of the faithful rising to God as well as sanctification, purification and reverence.

Greeting of the People

Those present join the priest in making the Sign of the Cross. This short prayer reminds us that we were baptized into God’s family, the Church as it expresses the two most important mysteries of our faith: the Holy Trinity and the cross, our redemption. We end the prayer by saying “Amen,” which means, “Yes, I believe.”

Greeting

The priest then greets us and welcomes everyone to church. He is speaking not only in his own name, but also in God’s name expressing his desire that the dynamic activity of God’s spirit be given to the people of God, enabling them to do the work of transforming the world as God has entrusted us. We respond to the priest using an ancient phrase, “And with your spirit” acknowledging his sacred ordination as we ask that the Holy Spirit give him the divine assistance that he needs to fulfill his prophetic call in the Church.

Act of Penance

Recalling one’s faults and sins, in preparation for the unity of the Eucharist, is an ancient tradition in the Church. We recall our common need for salvation and God’s merciful compassion. While this Act of Penance may occasionally involve a sprinkling with Holy Water (recalling our baptismal innocence), most often after a period of silence to call to mind our sins, we then ask for God’s mercy. In the recitation of the “Confiteor” or “I Confess,” we recognize publicly that we have sinned both in thought and deed and in sins of commission and omission, as we ask for the prayers of the community here present and all those in heaven with God. Using a gesture found in the Old Testament, we strike our breasts as a sign of our sorrow and an admission of guilt. We have no one to blame for our sins but ourselves. At the conclusion of the Act of Penance, the priest then says a prayer asking for God’s forgiveness and mercy that we may one day share in the fullness of eternal life.

Kyrie

The triple invocation: “Lord, have mercy; Christ, have mercy; Lord, have mercy.” is one of the oldest known prayers of the Mass. In Greek, the Church’s first official language, “Lord, have mercy” is “Kyrie eleison” and even throughout all the centuries when Latin became the Church’s language, the “Kyrie” was still prayed in Greek. An alternate form of the “Lord, have Mercy” may also used with preceding Christological exclamations about the person of Jesus Christ.

Gloria

Outside of Advent and Lent, we next offer a joyful hymn of praise to God called the Gloria. The first sentence of this prayer comes from the words the shepherds heard the angels sing the night Jesus was born: “Glory to God in the highest on earth peace to people of good will.” Written by the Early Church in the style of other canticles such as the Magnificat (Mary’s Hymn of Praise in the Gospel of Luke), the Gloria, as we know it today, and in the very same words we use today, is found in Christian prayer books as early as the year 380 AD! It is a hymn praising the Trinity for saving us from our sins.

Collect (Opening Prayer)

The following prayer, which concludes the introductory rites, has been given the name “Collect” from the Latin word “collecta” which means “to gather up.” In an ancient gesture of Christian worship, the priest assumes the posture of Christ on the cross as he gathers up the needs of the people and offers them to God in prayer. This prayer is almost always addressed to the Father, through the intercession of the Son, with the Holy Spirit.

LITURGY OF THE WORD

The focus of the Mass now shifts to ambo as the Liturgy of the Word begins. The readings are read at the ambo which was a teaching desk in ancient times. In this part of the Mass, we sit and listen to readings from the Bible. These readings tell us about God’s words, actions, and love for His people. The reading of Scripture has always been an integral part of the Liturgy. When the first Christians gathered to celebrate the Eucharist, they kept the Jewish custom of reading from Scripture. From the Hebrew Scriptures, they read the Books of the Law and the Prophets; they also shared letters written by early missionaries like Peter and Paul; and, of course, the Gospels.

First Reading

Except during the Easter Season, the First Reading is always taken from the Old Testament. The stories tell about God’s action in the world before Jesus was born and connect to the Gospel theme. The presence of the Old Testament in the first reading manifests the Church’s firm conviction that all Scripture is the Word of God. God is speaking to us in words of love through the whole Liturgy of the Word. There is continuity between the two Testaments or as St. Augustine said, “The New Testament lies hidden in the Old, and the Old becomes manifest in the New.” Both lead us to Jesus Christ so in general terms, the Old Testament is the promise, and the New Testament is the fulfilment. After each reading we pause in order to reflect and pray about what we have just heard.

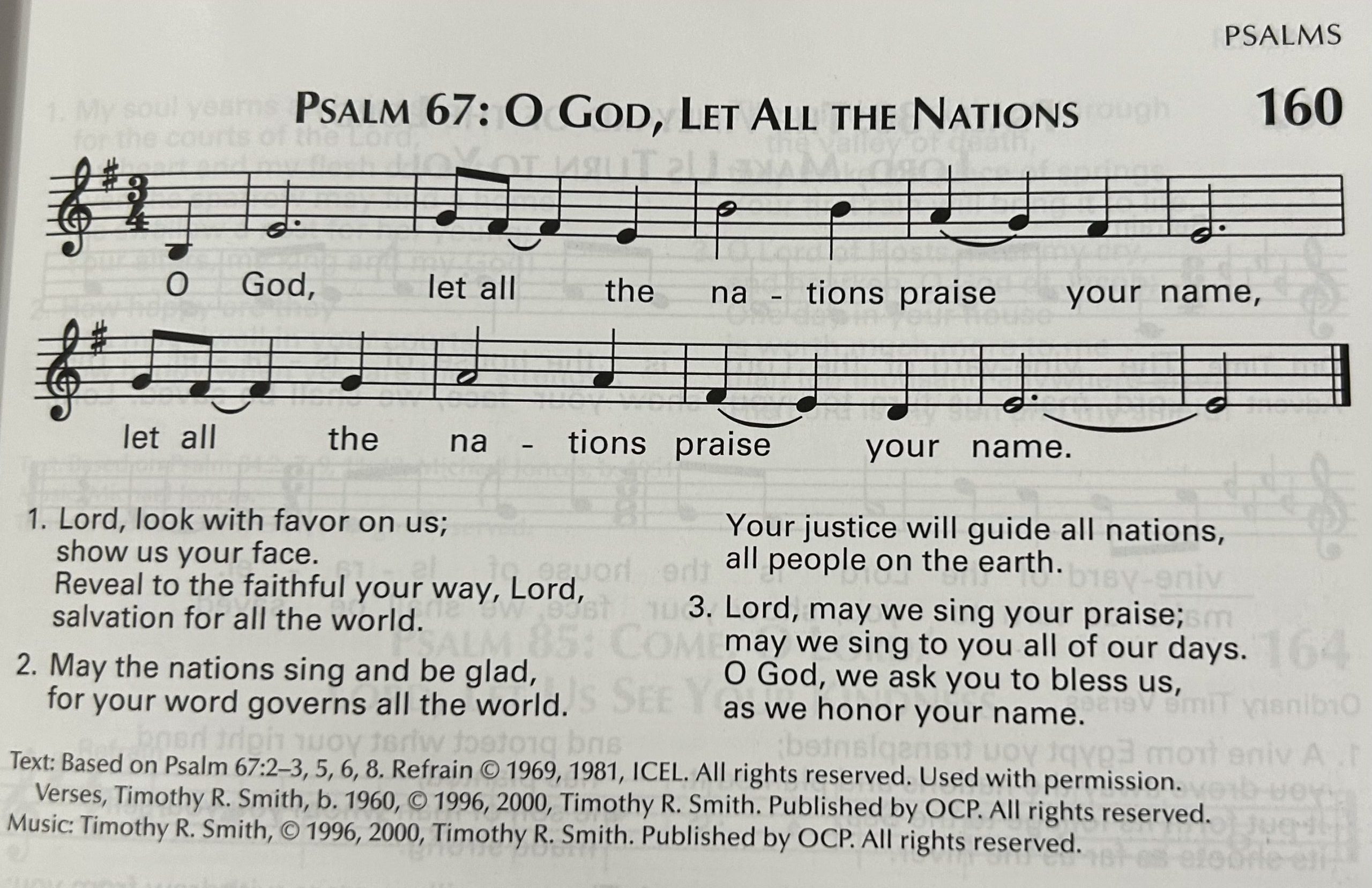

Responsorial Psalm

We then sing a song from the Book of Psalms that reflects the readings. Jesus quoted the Psalms more than any other Scripture. The Responsorial Psalm is primarily the Assembly’s response, in word or song, to the reading, which has just been proclaimed.

Second Reading (Epistle)

We now listen to a Second Reading which is always taken from the New Testament. This reading is called an “epistle” (i.e. letter) as it is taken from letters written by various apostles to the early Christian communities in different places in the ancient world. The second reading is usually from the same letter for several Sundays in a row. As St. Paul wrote nearly 30% of the New Testament, we most often read from one of his many letters. In these letters, we encounter the early Church living its Christian faith. This witness of the apostolic community provides an example for all times, since Christians of every age are to recall the love of the Father made present in Christ, the good news of redemption and the duty of Christian love.

Alleluia (Gospel Acclamation)

Outside of Lent, the Alleluia is then sung. It is expressive of Easter joy, recalling the Life, Death, Resurrection of Jesus. The Alleluia, which accompanies the Gospel procession, comes from a Hebrew word that means “Praise God.” The whole assembly praises Christ who comes to proclaim the Good News of salvation. During Lent an alternate acclamation is used. As this acclamation is sung, either the deacon receives a blessing to proclaim the Gospel worthily and well, or the Priest himself prays quietly before the altar and asks God to bless him so that he may effectively proclaim the Gospel. The Book of the Gospels, accompanied by candles, is taken from the Altar in solemn procession to the ambo.

Proclamation of the Gospel

The Gospel is very sacred since these are the words and deeds of Christ. We surround it by many distinct acts of respect; one of these is that we stand for the Gospel Reading. On special occasions, we use incense to reverence the Gospel. Whereas, any lector could proclaim the other readings, a special minister was appointed to read the Gospel. In the early Church it was the Deacon who was considered the special example of Christ as servant. Only in the absence of a Deacon does the Priest proclaim the Gospel. The making of three small signs of the Cross on one’s forehead, mouth and heart express readiness to open one’s mind to the Word, to confess it on our lips, and to safeguard it in the heart. We are then ready to listen to the Gospel.

Homily

We sit to listen attentively as the priest or deacon gives a reflection about the meaning of today’s readings called the homily. The homily, an integral part of the Liturgy of the Word, is a continuation of God’s saving message, which nourishes faith and conversion. It is more than just a sermon or talk about how we are to live or what we are to believe. It is a proclamation of God’s saving deeds in Christ. Just as a large piece of bread is broken to feed individual persons, the Word of God must be broken open so it can be received and digested by those present. After the homily, the priest sits for a brief time. This is time for us to think for us all to reflect about what has been asked of us during the homily.

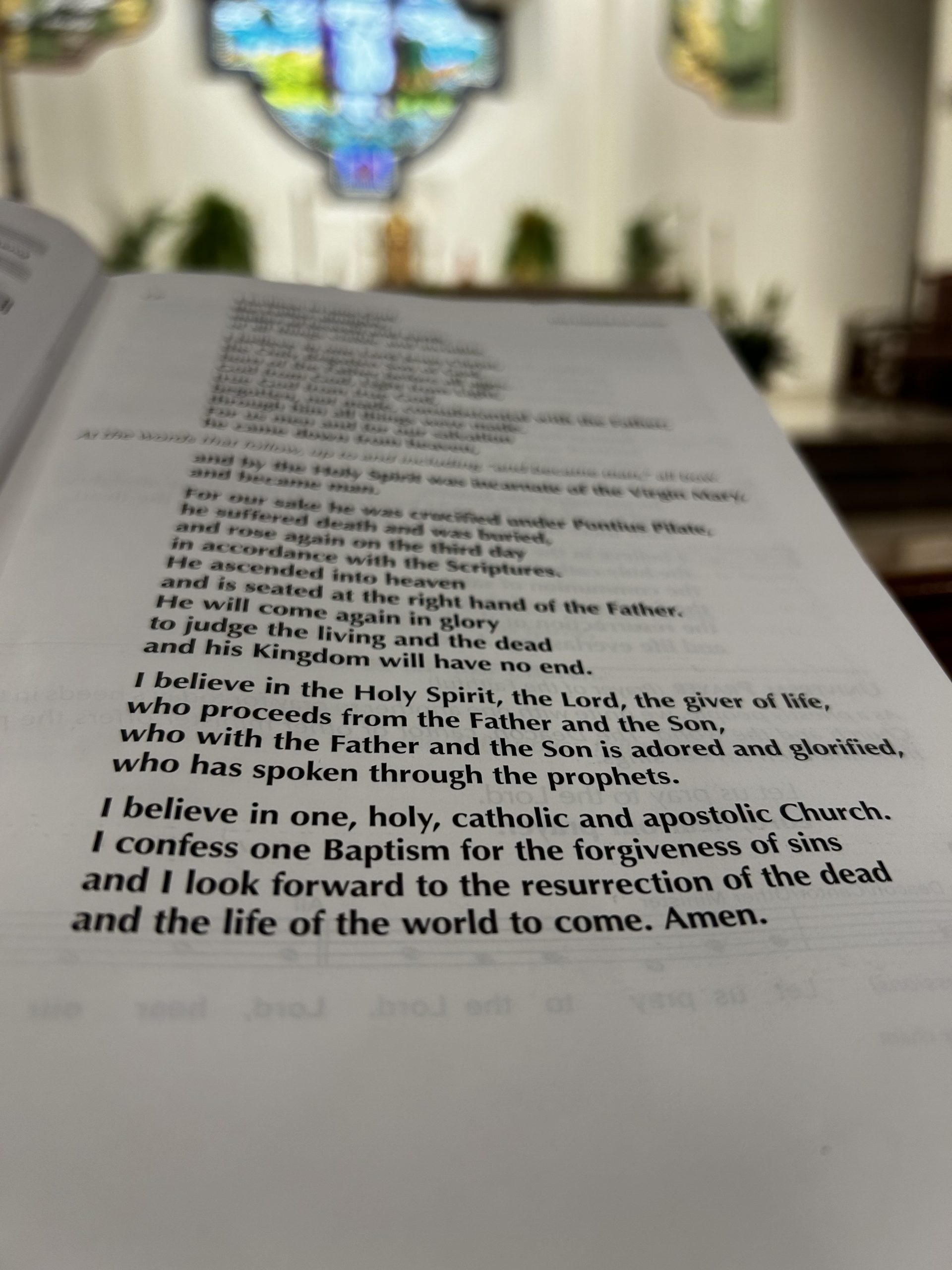

Profession of Faith (Creed)

We then stand to proclaim what we believe as Catholics as we renew our faith by reciting the Creed. In it, we are responding “Yes” to the message of God’s Word. The word creed comes from the first word of this statement, “Credo” or “I believe.” The oldest faith-statement in the Church is called the Apostle’s Creed. Likely from the First Century, it was highly prized as a summary of all Christian teaching. The Creed we use in the Liturgy today is an expansion of the Apostles Creed called the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed because of the two early Ecumenical Church Councils that developed it. The Creed, therefore, is a confession of faith that unites us with the Church throughout the world that briefly outlines our belief – in One God, a Trinity of three persons, the saving actions of God, and in His Holy Church. A third of the way through the creed, we bow at the words “by the Holy Spirit was incarnate of the Virgin Mary and became man” to honor and remember that key moment in time when God humbled Himself by entering into humanity to save us.

Universal Prayer

We close the Liturgy of the Word by praying the Universal Prayer, (formerly called the Prayers of the Faithful). We know from Paul’s letters that this custom of offering general intercessions existed in the earliest Christian communities. We pray for the Church, the world, and for a variety of special needs.

LITURGY OF THE EUCHARIST

The second major part of the Mass is called the Liturgy of the Eucharist. The gifts of bread and wine that show our thankfulness for all God has given us are brought to the altar. Gifts are collected for the care of the Church and for other special needs. During this part of the Mass, we watch as the altar is prepared for the miracle about to take place. The Liturgy of the Eucharist contains elements of two ancient traditions: the sacred meal which Jesus left as His memorial and the Hebrew tradition of sacrifice offered to God. The Mass therefore is the perpetuation of the Last Supper of Holy Thursday and the Sacrifice on the Cross of Good Friday.

Preparation of the Altar

Up until now, all of the actions have taken place away from the altar (either at the Priest’s chair or the ambo). Everything will now center on the altar where the Eucharistic Sacrifice will take place. The altar is prepared; the gifts are “set apart” and presented as a sign of the community’s desire to incorporate itself in the sacrifice of Christ.

Presentation of the Gifts

As early Christians brought bread and wine to be consumed at the Liturgy, along with money and other gifts to be given to the poor, so too we bring our gifts to the Altar. Jesus chose to use bread and wine because it was their everyday food yet also a symbol of celebration. Likewise, our bread and wine offered as gifts at Mass represents our everyday lives, but also foreshadows the great banquet of heaven. These gifts which have been brought to the altar as a symbol of our entire lives and challenge us to unite our whole life to the sacrifice of Christ, giving ourselves in thanksgiving for everything that God has given us.

Preparation of the Gifts

The priest presents to God the bread and then wine that will be used in the Eucharistic sacrifice. The priest mixes a little water with the wine to symbolize the human and the divine natures of Christ joined in the Mystery of the Incarnation – God becoming human. And giving us a share in his divinity or as St. Athanasius poetically said, “God became man so that man might become God.” Once again, incense may be used though in addition to the altar, the gifts, the priest, and the people are also incensed.

Lavabo (Washing of the Priest’s Hands)

With every meal we eat, we wash our hands. The priest now washes his hands as a symbol of internal purification to prepare for the most sacred part of the Mass. The priest then says a prayer over the gifts asking for God’s acceptance of our gifts and expresses our desire to be united with these gifts of bread and wine, which will become Jesus, our Lord.

The Preface of Eucharistic Prayer

Now we arrive at the most sacred part of the mass, the Eucharistic Prayer, “the center and high point to the entire liturgy.” It is essentially a prayer of praise and thanksgiving for God’s ultimate gift of salvation, making present both the Body and Blood of the Lord and His great redeeming actions in our lives. The priest prays to God on our behalf, but as a reminder that we are all offering this prayer, we first enter into a dialogue with the priest, making his prayer, which is Christ’s prayer, our own. The prayer following the dialogue (which varies by season and feasts), praises God the Father for His gifts of creation and redemption. God is ever faithful to His covenant. God’s saving deeds in the power of Christ are taking effect here and now!

Sanctus (Holy, Holy, Holy)

At the conclusion of this initial prayer, we respond by singing the Holy, Holy, Holy. Found in Isaiah’s sixth chapter, this is the song that the Angels and Saints sing forever before God in heaven. It was also a common morning song of praise in Jewish synagogues and the song which welcomed Jesus to Jerusalem at the time of His passion. As we recall all that Christ did and does for us, we join in this song together with the Church everywhere in Heaven and on Earth.

Eucharistic Prayer

We kneel for the Eucharistic Prayer because we are about to witness the holiest part of the Mass when Jesus becomes truly present on our altar. We kneel as the shepherds and kings did when they came to worship Jesus in Bethlehem. Our main prayer at each Eucharist is for unity with God and neighbor that is a result of the reconciliation won for us by Christ, which we participate in by the offering our whole life to the Father with and through Christ. We should always listen to these prayers with the greatest of reverence as if we are hearing them for the first time.

Epiclesis

During this prayer, the priest places his hands over the bread and wine to be blessed. This action, called the Epiclesis, calls down the Holy Spirit upon the bread and wine, so that it might be changed into the Body and Blood of Christ. He then blesses the bread and wine to be transformed by making the sign of the cross over them.

Institution Narrative

The words of consecration, which follow, are taken from the accounts of the Last Supper in Sacred Scripture, known as the Institution Narrative. As the bread and wine are actually changed into Christ’s Body and Blood, the priest raises each for adoration. The priest then genuflects each time after he says the words of consecration. He is adoring Jesus and acknowledging the holy presence of Our Lord. We too, should bow our heads and adore Jesus silently in our hearts.

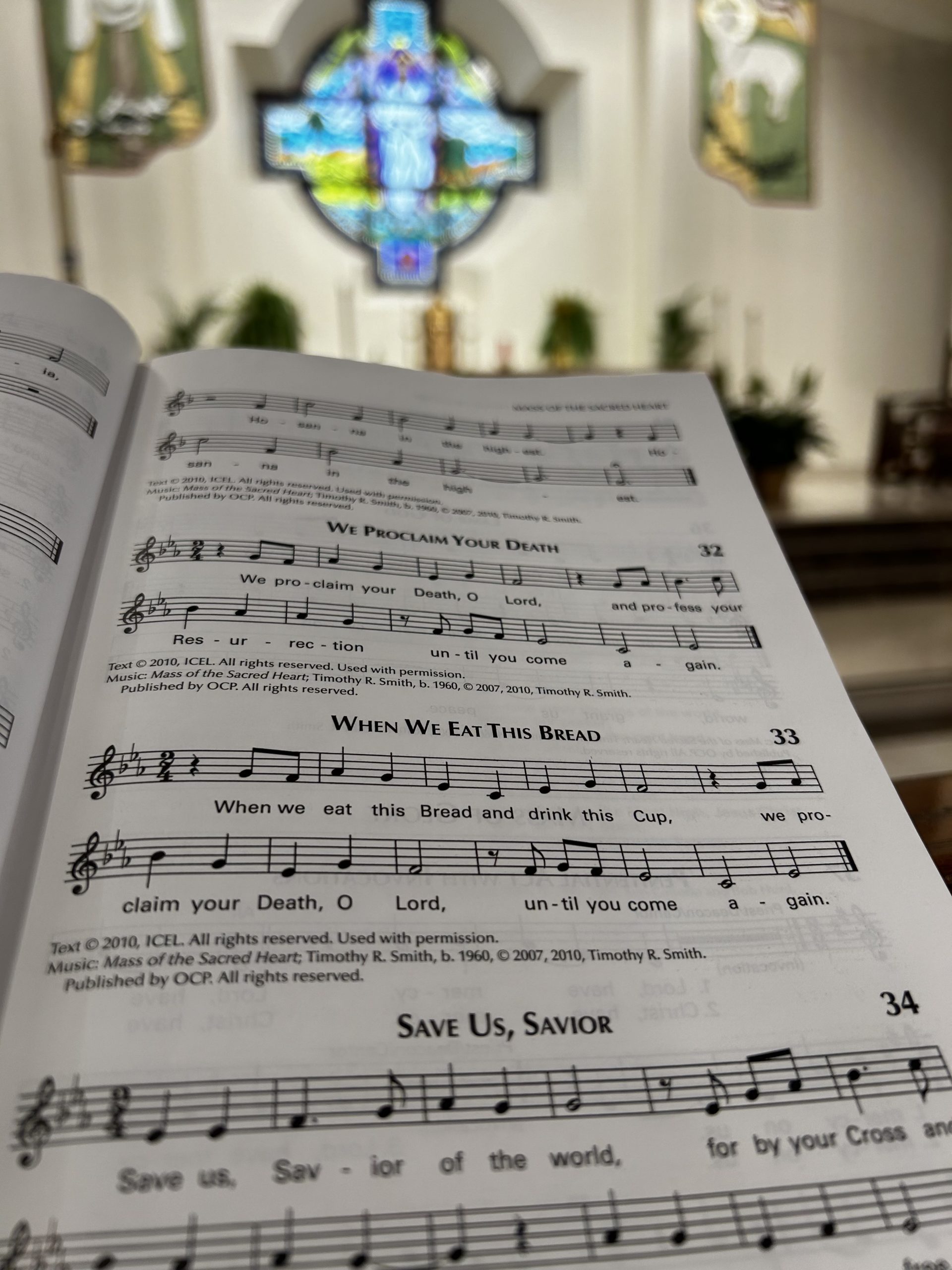

Anamnesis

As Jesus is truly present now under the appearances of bread and wine, this mystery of our faith is proclaimed in the Anamnesis or Memorial Acclamation by which we recall the command we received from Christ the Lord through the apostles, to celebrate the memorial of Christ, by recalling His passion, death and resurrection.

Oblation and Intercessions

The Eucharistic Prayer continues with the oblation as the priest leads all gathered to offer the unblemished sacrificial victim in the Holy Spirit to the Father. We pray that we may all learn to offer ourselves day by day to God as we seek to be in union with Him and each other through the meditation of Christ Jesus. The priest continues to pray in the intercessions for all people, living and dead, and for the leaders of the Church, through the intercession of the Blessed Mother and all the saints.

Concluding Doxology

At the conclusion of the Eucharistic Prayer, we join the priest in giving glory to God the Father through Jesus our Savior and the Holy Spirit in a statement of praise called a doxology. The Doxology which in Greek means “words of praise” summarize the saving actions of Christ as manifested in the Eucharistic Prayer. The priest elevates the Body and Blood of Christ for all to see while giving all glory to God: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Our great Amen to this prayer acclaims our assent and our participation in the entire Eucharistic Prayer, which has made Christ present and is the center of our Catholic faith.

The Lord’s Prayer

We prepare to receive Jesus in the Eucharist by praying together the prayer that Jesus taught us. The Lord’s Prayer is truly the summary of the whole gospel. Its original proclamation is from the Sermon on the Mount in which Jesus teaches us not just how to pray, but how to live as we await the fullness of His kingdom. This prayer not only teaches us what things to ask for, but also in what order we should desire them. This prayer that comes to us from Jesus is truly unique. On the one hand, the only Son gives us the words His Father gave Him. He is the master of our prayer. On the other hand, Christ, as the Word made flesh, knows in His human heart the needs of His human sisters and brothers, and reveals them to us. He is the model of our prayer. Through this prayer, we place ourselves in the presence of God – to adore, to love and to praise Him. As we ask that our lives be nourished, healed of sin, and made victorious in the struggle of good over evil.

Embolism

At the end of the Lord’s Prayer, the priest develops the last petition of the Our Father in a brief prayer asking that Christ will make us victorious in the present struggle of good over evil. Our response reflects once again the first part of the “Our Father” giving the kingship, the power and the glory to Our Father.

Rite of Peace

Before we approach the altar of God, we need to be reconciled with our neighbors. This is called the Sign of Peace. The Sign of Peace has been part of the Mass as early as the fourth century. We pray that each person will live in total and complete harmony with God and others. In the sign of peace, we make a spiritual pledge to be open to each other as Christ would, both in the celebration of the Liturgy and after it. It is only the Risen Christ who is the source of all peace.

Fraction Rite

As the Lamb of God is sung, the priest takes the host and breaks it over the chalice or paten. This is something that Jesus did at the Last Supper, the apostles did after the resurrection and the Church has been doing ever since. A small portion of the large host will then be placed into the chalice signifying the union of the Body and the Blood of Christ. Just as the double consecration, that is, of the bread and of the wine, represented the death of Christ, so it was deemed necessary to symbolize the reuniting of the Body and Blood of Christ before communion – a symbolic re-enactment of the Lord’s resurrection.

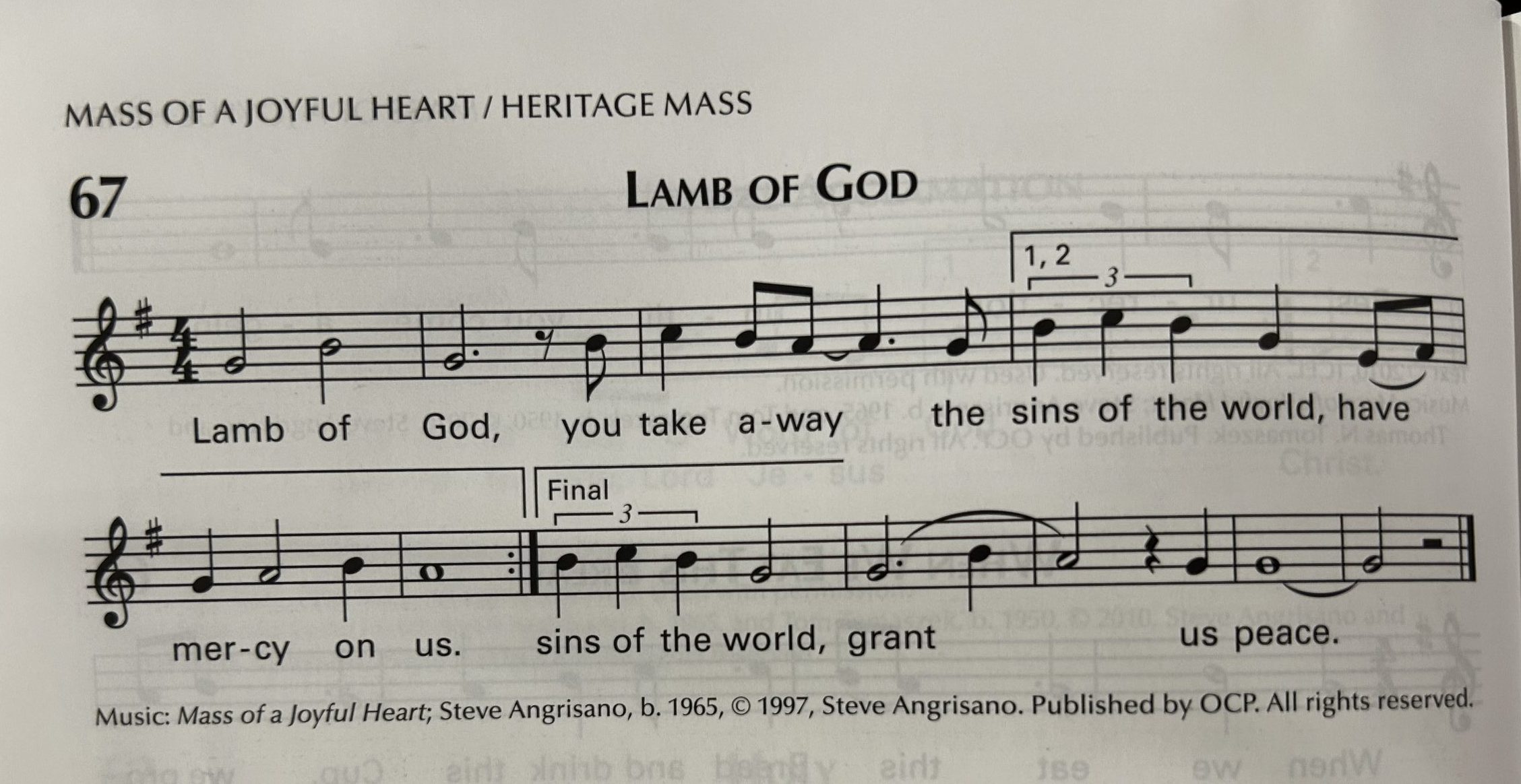

Lamb of God

Meanwhile the Lamb of God, a litany-type acclamation accompanies the breaking of the Sacred Host. Jesus is literally “broken for us” for our salvation. Similarly, we are expected to offer our lives for others in the same way Jesus did throughout His life and especially in the passion.

Private Prayers of the Priest

The priest prepares himself by a prayer said quietly that he may faithfully receive the Body and Blood of Christ and live out his priestly vocation in fidelity and love.

Presentation of the Eucharistic Species

The priest now raises the Body and Blood of Jesus for all to see and adore using the words of John the Baptist who pointed out Jesus to others as well as referring to the Banquet of Lamb from the Book of Revelation. We call upon Jesus to prepare us so that we might be ready to receive Holy Communion as we respond with the same words used by the soldier who approached Jesus to cure his servant.

Holy Communion

After the priest, extraordinary communion ministers and servers receive Holy Communion, those who share our Catholic faith and are properly disposed are then invited to receive the Eucharist. It is very important that we remind ourselves of what we are about to do: we are going to receive the Body and Blood of Our Lord! We should receive the Eucharist because we want to be one with Jesus and we want to be like him. When you approach the priest or extraordinary minister, bow as a sign of reverence and respond by saying “Amen” which indicates that you truly believe you are about to receive the Son of God. When you return to your pew, after you receive Communion, kneel and pray. Thank God for the many gifts he has given you and for all the people you love. Ask Jesus for what you need and pray for others. Pray quietly, sing, and remain kneeling until what remains of the Blessed Sacrament is placed in tabernacle and closed.

Prayer after Communion

After a time of silence, all stand as the Priest prays that the reception of Holy Communion will result in certain and definite spiritual benefits for those who have shared the Eucharist – that the spiritual effects of the Eucharist will be carried out in our everyday lives.

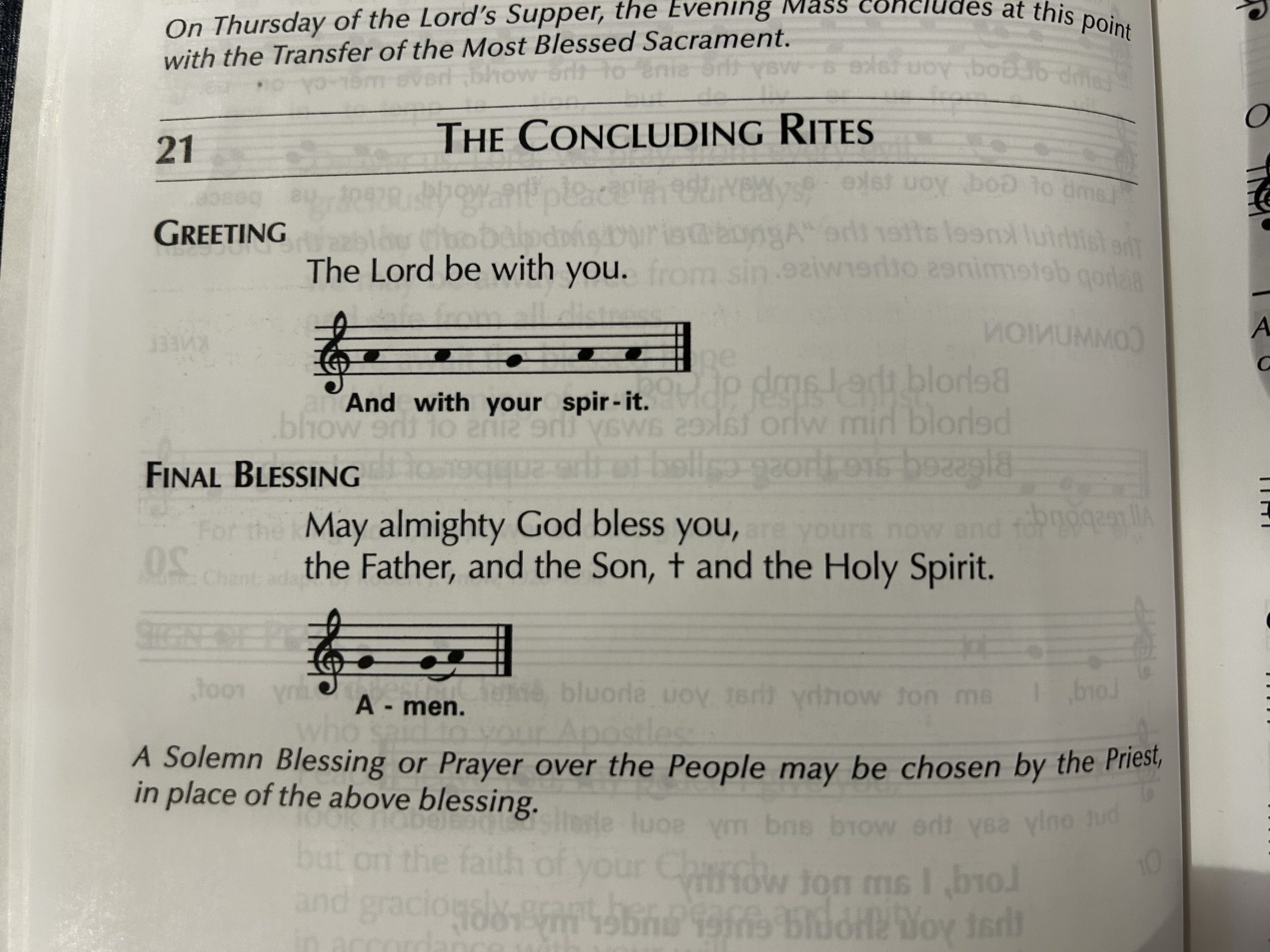

Final Blessing

The Priest says again “The Lord be with you.” This ritual phrase now serves as a farewell, followed by a blessing. The trinitarian blessing prays that the grace God has given us in this part of our lives will benefit us because this is what we sacrificed with Christ in the Eucharist to the Father through the Holy Spirit.

Dismissal

The deacon (or in his absence the priest) then dismisses the people. The words in Latin Ite, missa est (Go, you are sent) is where the word “mass” actually comes from as we are sent forth to carry the love of Jesus to everyone we meet so that we can become what we have eaten: the Body and Blood of Jesus for others.

Reverence of the altar and departure

The priest now reverences the altar once again as he did when he began the Liturgy. It is similar to how we might say goodbye to a close friend or relative. Kissing the altar is a gesture of intimacy venerating Christ symbolized by the altar. Typically, some type of music accompanies the priest and liturgical ministers as they depart the sanctuary. We leave Church after we celebrate Mass, knowing that the Lord will help us show love and kindness to others.